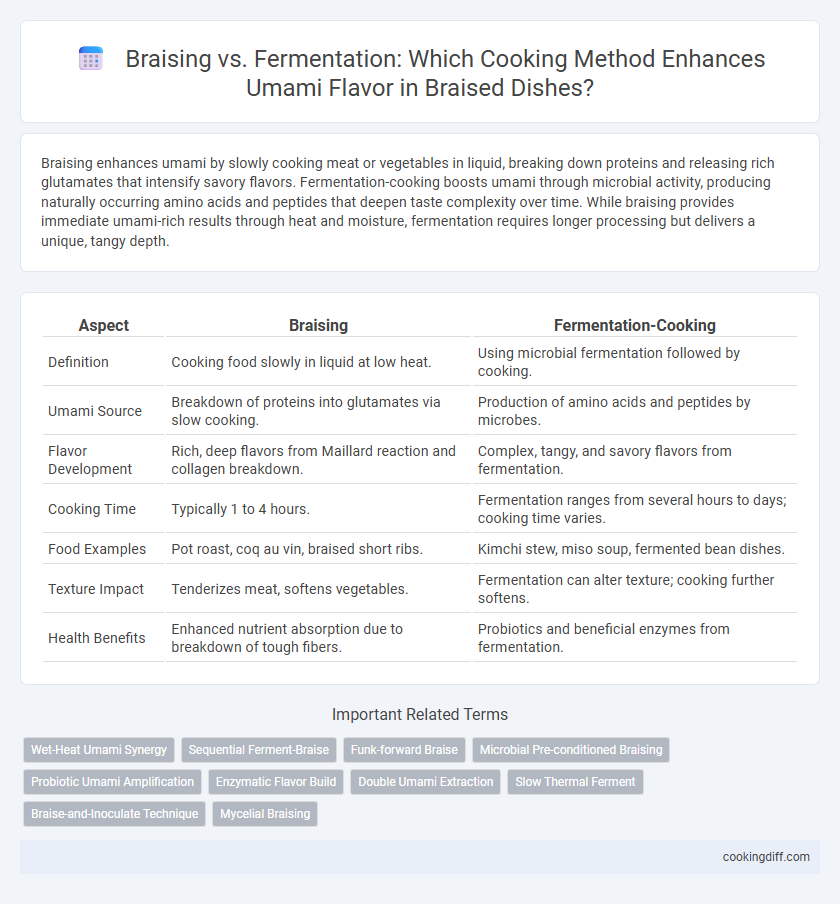

Braising enhances umami by slowly cooking meat or vegetables in liquid, breaking down proteins and releasing rich glutamates that intensify savory flavors. Fermentation-cooking boosts umami through microbial activity, producing naturally occurring amino acids and peptides that deepen taste complexity over time. While braising provides immediate umami-rich results through heat and moisture, fermentation requires longer processing but delivers a unique, tangy depth.

Table of Comparison

| Aspect | Braising | Fermentation-Cooking |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Cooking food slowly in liquid at low heat. | Using microbial fermentation followed by cooking. |

| Umami Source | Breakdown of proteins into glutamates via slow cooking. | Production of amino acids and peptides by microbes. |

| Flavor Development | Rich, deep flavors from Maillard reaction and collagen breakdown. | Complex, tangy, and savory flavors from fermentation. |

| Cooking Time | Typically 1 to 4 hours. | Fermentation ranges from several hours to days; cooking time varies. |

| Food Examples | Pot roast, coq au vin, braised short ribs. | Kimchi stew, miso soup, fermented bean dishes. |

| Texture Impact | Tenderizes meat, softens vegetables. | Fermentation can alter texture; cooking further softens. |

| Health Benefits | Enhanced nutrient absorption due to breakdown of tough fibers. | Probiotics and beneficial enzymes from fermentation. |

Introduction to Umami: Defining the Fifth Taste

Umami, recognized as the fifth basic taste, is characterized by a savory, broth-like flavor predominantly found in foods rich in glutamates and nucleotides. Braising enhances umami by breaking down proteins and releasing amino acids during slow cooking, creating deep, complex flavors. In contrast, fermentation-cooking intensifies umami through microbial activity that produces glutamic acid and other flavor compounds over time.

Braising: Techniques for Deep Flavor Development

Braising employs low, slow cooking with moist heat to break down collagen in meats, resulting in tender textures and concentrated umami flavors. This technique integrates Maillard reaction and simmering in seasoned liquids, maximizing deep, savory taste development.

- Collagen Breakdown - Slow cooking at low temperatures transforms tough connective tissues into gelatin, enhancing mouthfeel and richness.

- Maillard Reaction - Initial searing creates complex flavor compounds that intensify umami before the braising liquid infuses the dish.

- Moist Heat Infusion - Braising liquids enriched with umami-rich ingredients penetrate the protein, fostering deep, layered savory notes.

Fermentation in Cooking: Harnessing Microbial Magic

Fermentation in cooking leverages beneficial microbes to transform raw ingredients, unlocking complex umami flavors through natural enzymatic processes. This microbial magic breaks down proteins into amino acids like glutamate, enhancing savory taste profiles beyond what traditional braising achieves.

Unlike braising, which uses slow cooking with moisture to tenderize food and develop flavor, fermentation relies on time and microbial activity to generate depth and richness in dishes. Chefs harness these microorganisms to create sauces, pastes, and condiments that intensify umami without heat application.

Key Differences: Braising vs Fermentation Processes

Braising involves slow cooking meat or vegetables in liquid at low temperatures, which breaks down connective tissues and enhances savory flavors through Maillard reactions. Fermentation relies on microbial activity to transform sugars into acids, alcohols, and other compounds, intensifying umami by producing glutamates and peptides.

Braising is a thermal process emphasizing collagen breakdown and flavor development via heat, requiring controlled temperature and time. Fermentation is a biochemical process that enhances umami through enzymatic reactions and natural probiotics, often involving longer durations and specific microbial cultures.

Ingredient Selection: Best Choices for Braising vs Fermentation

| Cooking Method | Ideal Ingredients | Umami Enhancement Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Braising | Meats with connective tissues (beef shank, pork shoulder), root vegetables (carrots, onions), mushrooms (shiitake, cremini) | Selection of collagen-rich cuts and umami-rich aromatics maximizes glutamate release during slow cooking |

| Fermentation | Vegetables (cabbage, cucumbers), legumes (soybeans), seafood (anchovies), grains (barley) | Microbial activity increases free amino acids like glutamate and nucleotides, enhancing deep umami flavors |

How Braising Enhances Umami: Science & Methods

Braising intensifies umami by breaking down proteins into glutamates through slow cooking in moist heat, unlike fermentation which develops umami via microbial activity. The controlled temperature and liquid environment in braising facilitate the release of amino acids, enriching flavor complexity.

- Protein Breakdown - Slow braising denatures proteins, releasing glutamic acid which enhances umami taste.

- Maillard Reaction - Browning meat before braising produces additional flavor compounds that deepen umami intensity.

- Flavor Infusion - Braising liquid absorbs and concentrates savory compounds, amplifying overall umami sensation.

Fermentation for Umami: Cultures, Enzymes, and Taste

Fermentation for umami enhancement relies on specific microbial cultures such as Lactobacillus and Aspergillus, which produce enzymes that break down proteins into amino acids like glutamate, the key compound responsible for umami flavor. These enzymes accelerate the development of complex taste profiles by converting peptides and nucleotides, enriching the dish with savory depth that braising alone cannot achieve. The controlled environment of fermentation allows precise modulation of umami intensity, making it an essential technique in culinary practices aiming for enhanced flavor complexity.

Culinary Applications: Classic Dishes Featuring Each Method

Braising intensifies umami through slow cooking in liquid, commonly seen in dishes like coq au vin and pot roast. Fermentation-cooking develops umami via microbial action, showcased in miso soup and kimchi jjigae.

- Braising in classic dishes - Braised short ribs use a flavorful broth to break down collagen, enhancing savory depth.

- Fermentation-cooking in classic dishes - Natto's fermented soybeans provide a pungent, umami-rich taste fundamental to Japanese cuisine.

- Texture and flavor contrast - Braising offers tender, rich meats while fermentation-cooking yields bold, tangy flavors through fermentation byproducts.

Both techniques unlock umami but cater to distinct culinary traditions and flavor profiles.

Health and Nutrition: Comparing Braising and Fermentation

How do braising and fermentation compare in enhancing umami while supporting health and nutrition? Braising gently breaks down proteins and carbohydrates through slow cooking, preserving nutrients and enhancing natural umami flavors without adding microbes. Fermentation enriches umami by producing glutamates and beneficial probiotics, promoting gut health and improving nutrient absorption through microbial activity.

Related Important Terms

Wet-Heat Umami Synergy

Braising combines prolonged wet heat with connective tissue breakdown, intensifying umami through glutamate release and Maillard reactions in moist environments. Fermentation-cooking enhances umami by generating free amino acids and peptides via microbial enzymatic activity, but braising's wet-heat method creates a synergistic umami profile by balancing savory depth and tender texture.

Sequential Ferment-Braise

Sequential ferment-braise maximizes umami by combining fermentation's enzymatic breakdown of proteins into amino acids with braising's slow, moist heat that intensifies savory flavor compounds. This method leverages fermentation to increase glutamate levels before braising, resulting in deeper, richer taste profiles unmatched by either technique alone.

Funk-forward Braise

Funk-forward braising intensifies umami by slow-cooking proteins in savory, acidic liquids, promoting Maillard reactions and collagen breakdown that deepen flavor complexity beyond traditional fermentation-cooking methods. While fermentation cultivates umami through microbial transformation of amino acids, braising achieves a robust, rich taste profile by concentrating glutamates and nucleotides in meat fibers and surrounding braising liquids.

Microbial Pre-conditioned Braising

Microbial pre-conditioned braising enhances umami by utilizing controlled microbial activity to develop rich amino acid profiles before traditional slow cooking, intensifying savory flavors beyond typical fermentation-cooking methods. This process combines enzymatic breakdown from microbes with heat-induced Maillard reactions, creating complex taste compounds that significantly boost the depth of umami in braised dishes.

Probiotic Umami Amplification

Braising enhances umami through slow cooking that breaks down proteins into savory amino acids like glutamate, enriching flavor complexity without altering probiotic content. Fermentation-cooking amplifies probiotic umami by introducing beneficial bacteria that produce organic acids and peptides, simultaneously boosting gut health and deepening savory taste profiles.

Enzymatic Flavor Build

Braising enhances umami through slow cooking at low temperatures, allowing natural enzymes to break down proteins into flavorful amino acids like glutamate. Fermentation-cooking relies on microbial enzymatic activity to generate intense umami compounds, producing complex flavors through prolonged biochemical transformations.

Double Umami Extraction

Braising and fermentation-cooking both enhance umami through different mechanisms, with braising extracting glutamates and nucleotides via slow, moist heat, while fermentation develops these compounds through microbial activity. Combining braising with fermentation maximizes double umami extraction, intensifying savory depth by leveraging amino acid breakdown and organic acid production.

Slow Thermal Ferment

Slow Thermal Ferment enhances umami by using controlled microbial fermentation combined with low-temperature cooking, allowing complex flavor compounds to develop over extended periods. Braising, relying on slow cooking with moisture, primarily tenderizes meat and integrates flavors but lacks the biochemical transformation of amino acids and peptides achieved through Slow Thermal Ferment.

Braise-and-Inoculate Technique

Braise-and-Inoculate technique combines the slow, moist heat of braising with targeted fermentation to amplify umami by promoting the growth of beneficial microbes that intensify flavor precursors. This hybrid method enhances amino acid release and savory depth beyond traditional braising, creating a rich, complex taste profile ideal for gourmet cooking.

Braising vs Fermentation-cooking for umami enhancement. Infographic

cookingdiff.com

cookingdiff.com