Braising involves cooking food slowly in liquid at low temperatures, resulting in tender, moist textures as collagen breaks down and fibers soften. Slow roasting uses dry heat at low temperatures, which develops a browned, crispy exterior while maintaining a firmer interior texture. The choice between braising and slow roasting depends on whether a juicy, fall-apart finish or a contrast between crisp outside and tender inside is desired.

Table of Comparison

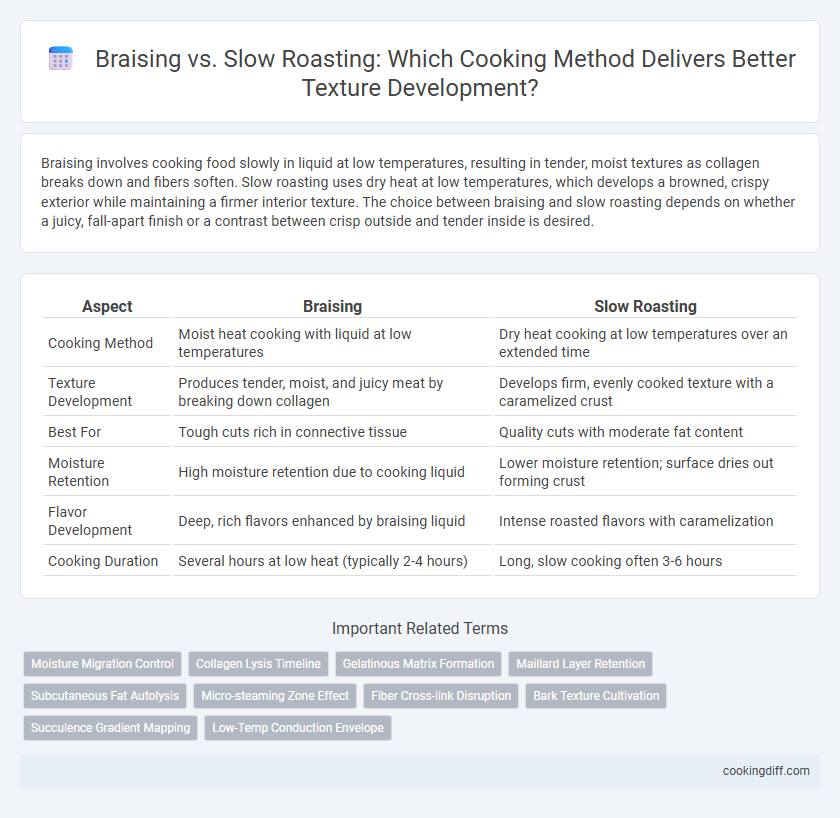

| Aspect | Braising | Slow Roasting |

|---|---|---|

| Cooking Method | Moist heat cooking with liquid at low temperatures | Dry heat cooking at low temperatures over an extended time |

| Texture Development | Produces tender, moist, and juicy meat by breaking down collagen | Develops firm, evenly cooked texture with a caramelized crust |

| Best For | Tough cuts rich in connective tissue | Quality cuts with moderate fat content |

| Moisture Retention | High moisture retention due to cooking liquid | Lower moisture retention; surface dries out forming crust |

| Flavor Development | Deep, rich flavors enhanced by braising liquid | Intense roasted flavors with caramelization |

| Cooking Duration | Several hours at low heat (typically 2-4 hours) | Long, slow cooking often 3-6 hours |

Understanding Braising and Slow Roasting

Braising involves cooking food slowly in a small amount of liquid, which helps break down collagen and results in tender, moist textures. Slow roasting uses dry heat to gently cook food over an extended period, preserving natural juices and creating a caramelized exterior. Both methods enhance texture development but braising emphasizes moisture retention, while slow roasting focuses on surface browning and flavor concentration.

The Science of Texture in Cooking

Braising uses low heat and moisture to break down collagen into gelatin, resulting in tender, moist textures ideal for tougher cuts of meat. Slow roasting applies dry heat over extended periods, concentrating flavors while developing a firmer, drier crust and a more fibrous interior texture.

- Braising enhances collagen breakdown - Moist heat at 160-180degF promotes gelatin formation, softening connective tissues for a silky mouthfeel.

- Slow roasting encourages Maillard reactions - Dry heat above 250degF creates complex flavor compounds and crisp exterior textures.

- Texture outcomes differ significantly - Braising yields uniformly tender and juicy meat, whereas slow roasting develops structured, chewy bites with concentrated flavors.

Moist Heat vs Dry Heat: Key Differences

How does moist heat in braising compare to dry heat in slow roasting for texture development? Braising uses moist heat that breaks down collagen in tough cuts, resulting in tender, juicy meat. Slow roasting employs dry heat that dries out the surface, creating a crispy exterior while maintaining a firmer interior texture.

How Braising Develops Tenderness

Braising develops tenderness by cooking meat slowly in liquid at low temperatures, which breaks down collagen into gelatin, resulting in a moist, tender texture. Slow roasting cooks meat with dry heat, leading to a firmer texture as collagen breaks down less effectively due to the lack of moisture.

- Collagen Breakdown - Braising transforms tough collagen fibers into soft gelatin through a moist, low-heat process.

- Moisture Retention - The liquid environment in braising maintains moisture, preventing the meat from drying out during cooking.

- Temperature Control - Low and steady temperatures in braising enable gradual tenderization without toughening muscle fibers.

This method consistently produces tender, flavorful meat compared to the drier texture resulting from slow roasting.

The Role of Slow Roasting in Texture Formation

Slow roasting enhances texture formation by gradually breaking down muscle fibers and connective tissues, resulting in tender yet firm meat. The consistent low heat allows collagen to convert into gelatin without drying out the outer layers, preserving juiciness.

In contrast to braising, slow roasting relies on dry heat, which develops a caramelized crust that adds complexity to the texture. This method emphasizes a balance between tenderness and surface crispness, ideal for cuts with moderate fat content.

Comparing Meat Fiber Breakdown

Braising involves cooking meat slowly in liquid at low temperatures, which facilitates collagen breakdown into gelatin, resulting in tender, moist fibers. Slow roasting, while also low and slow, relies primarily on dry heat to gradually soften meat fibers but may retain firmer textures compared to braising.

Meat fiber breakdown in braising is enhanced by the presence of moisture, which helps collagen dissolve more effectively, producing a silkier mouthfeel. Slow roasting can develop complex flavors through Maillard reactions but typically preserves more fibrous texture due to lack of liquid. The choice between braising and slow roasting directly impacts the tenderness and juiciness of tougher cuts.

Flavor Concentration: Braising vs Slow Roasting

Braising enhances flavor concentration by cooking food slowly in a small amount of liquid, which breaks down connective tissues and infuses the dish with rich, deep flavors. This moist heat method locks in moisture, resulting in tender textures and intensified taste profiles.

Slow roasting relies on dry heat over an extended period, which concentrates flavors through caramelization and Maillard reactions without added liquid. This technique produces a crispy exterior and a firmer texture while developing complex, roasted flavors.

Best Ingredients for Each Method

Braising works best with tougher cuts like beef chuck, pork shoulder, and short ribs, as the slow cooking in liquid breaks down collagen, resulting in tender, flavorful meat. Slow roasting is ideal for tender cuts such as prime rib, pork loin, and whole chicken, preserving juiciness while developing a crispy, browned exterior. Choosing the right ingredient enhances texture development: braising transforms fibrous cuts into melt-in-your-mouth dishes, while slow roasting highlights the natural tenderness and surface caramelization of premium meats.

Common Pitfalls Affecting Texture

Braising and slow roasting both aim to develop tender textures but often face challenges that compromise the final result. Mismanaging heat and moisture levels are common pitfalls that negatively impact texture development in these cooking methods.

- Overcooking - Prolonged cooking times can cause braised meat to become mushy, while slow roasting may dry out the exterior and toughen the interior.

- Insufficient Moisture - Braising without enough liquid results in uneven cooking and toughness, unlike slow roasting, which relies on dry heat but requires controlled humidity to maintain juiciness.

- Inconsistent Temperature - Fluctuating heat during braising can hinder collagen breakdown, and in slow roasting, irregular oven temperatures lead to uneven texture development.

Related Important Terms

Moisture Migration Control

Braising controls moisture migration by cooking food in a small amount of liquid at low temperatures, resulting in tender, juicy textures due to the slow breakdown of connective tissues. Slow roasting uses dry heat, which can cause more moisture loss and a firmer texture, making braising superior for retaining succulence and ensuring even moisture distribution throughout the food.

Collagen Lysis Timeline

Braising achieves collagen lysis between 160degF and 205degF over several hours, transforming tough connective tissues into tender gelatin and resulting in a moist, succulent texture. Slow roasting, typically performed at higher temperatures around 250degF to 300degF, causes collagen breakdown more rapidly but often leads to drier meat due to less moisture retention during the collagen lysis timeline.

Gelatinous Matrix Formation

Braising enhances texture development by breaking down collagen into a gelatinous matrix, resulting in tender, moist meat with rich mouthfeel. Slow roasting, although effective for even cooking, does not facilitate the same degree of collagen breakdown, leading to a firmer texture without the gelatinous succulence characteristic of braising.

Maillard Layer Retention

Braising preserves a moist environment that enhances collagen breakdown and retains a tender texture while maintaining a pronounced Maillard crust due to initial searing. Slow roasting develops deep flavor through prolonged dry heat but risks diminishing the Maillard layer, resulting in less surface caramelization and a drier exterior.

Subcutaneous Fat Autolysis

Braising promotes subcutaneous fat autolysis through prolonged exposure to low, moist heat, breaking down collagen and rendering fat into tender, juicy textures. Slow roasting, while also breaking down fat, tends to preserve firmer textures due to dry heat, resulting in a contrasting mouthfeel and less fat autolysis.

Micro-steaming Zone Effect

Braising creates a micro-steaming zone within the cooking vessel by trapping moisture, which breaks down collagen and tenderizes meat more efficiently than slow roasting, which uses dry heat and lacks this localized moisture environment. The retained steam in braising enhances texture development by promoting cellular breakdown, resulting in juicier, more tender cuts compared to the firmer texture produced by slow roasting.

Fiber Cross-link Disruption

Braising effectively breaks down tough muscle fibers through prolonged exposure to moist heat, promoting significant fiber cross-link disruption and resulting in tender, succulent textures. In contrast, slow roasting uses dry heat which gradually cooks meat but causes less fiber cross-link breakdown, often yielding a firmer texture with less pronounced tenderness.

Bark Texture Cultivation

Braising cultivates a tender, moist bark by slow cooking meat in liquid at low temperatures, promoting collagen breakdown and flavor infusion, whereas slow roasting develops a firmer, drier bark through prolonged dry heat, enhancing Maillard reactions for a crisp exterior. The choice between braising and slow roasting directly influences bark texture, with braising yielding a softer, gelatinous crust and slow roasting producing a robust, caramelized bark ideal for textured contrast.

Succulence Gradient Mapping

Braising creates a pronounced succulence gradient through prolonged moisture immersion, preserving juiciness from the surface to the center by breaking down collagen into gelatin. Slow roasting develops texture via gentle, even heat that promotes uniform moisture retention but results in a less distinct succulence gradient compared to braising.

Braising vs Slow Roasting for texture development Infographic

cookingdiff.com

cookingdiff.com