Miso and natto are both traditional Japanese fermented soybean products, but they differ significantly in fermentation processes and flavor profiles. Miso is made by fermenting soybeans with koji mold, resulting in a smooth, savory paste often used in soups and sauces, while natto is produced by fermenting soybeans with Bacillus subtilis, giving it a sticky texture and strong, pungent aroma. Miso offers milder taste and versatility in cooking, whereas natto is prized for its unique texture, high probiotic content, and health benefits.

Table of Comparison

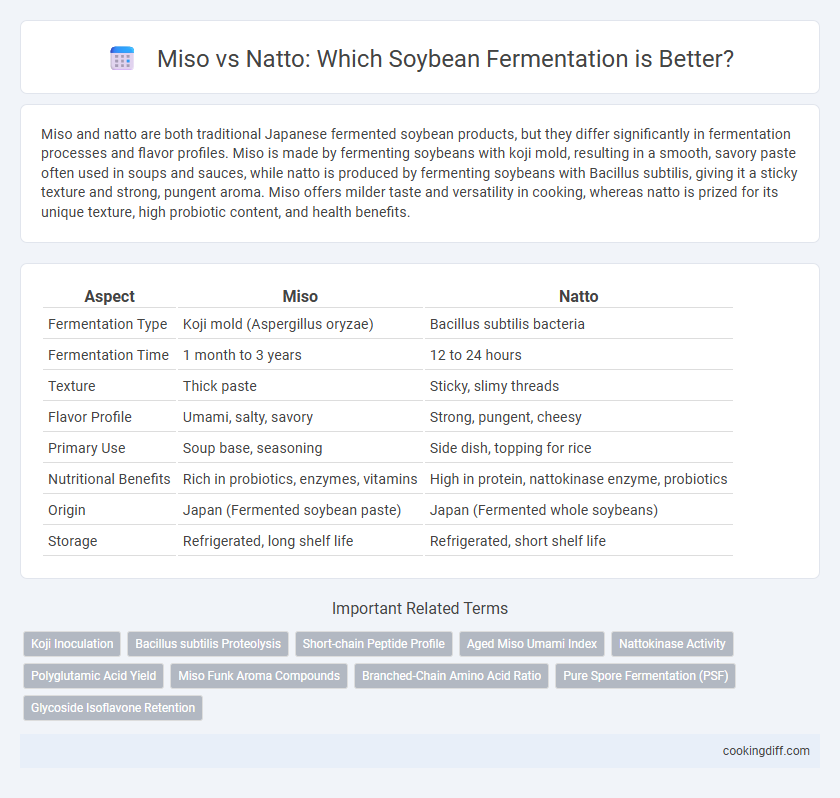

| Aspect | Miso | Natto |

|---|---|---|

| Fermentation Type | Koji mold (Aspergillus oryzae) | Bacillus subtilis bacteria |

| Fermentation Time | 1 month to 3 years | 12 to 24 hours |

| Texture | Thick paste | Sticky, slimy threads |

| Flavor Profile | Umami, salty, savory | Strong, pungent, cheesy |

| Primary Use | Soup base, seasoning | Side dish, topping for rice |

| Nutritional Benefits | Rich in probiotics, enzymes, vitamins | High in protein, nattokinase enzyme, probiotics |

| Origin | Japan (Fermented soybean paste) | Japan (Fermented whole soybeans) |

| Storage | Refrigerated, long shelf life | Refrigerated, short shelf life |

Introduction to Soybean Fermentation: Miso vs Natto

Fermenting soybeans transforms their nutritional profile and digestibility through unique microbial processes. Miso and natto represent two traditional Japanese fermented soybean products distinguished by their fermentation agents and flavors.

- Miso - Fermented using Aspergillus oryzae, miso produces a savory paste with a rich umami taste and smooth texture.

- Natto - Fermented by Bacillus subtilis natto, natto is characterized by its sticky texture and strong, pungent aroma.

- Health benefits - Both offer probiotics, enhanced protein digestibility, and bioavailable nutrients, but differ in flavor profiles and culinary uses.

Origins and History: Miso and Natto

Miso and natto are traditional Japanese fermented soybean products with distinct origins and historical developments. Miso dates back to ancient China before evolving in Japan around the 7th century, while natto has been a staple in Japan since at least the Jomon period.

- Miso Origin - Miso fermentation began from Chinese techniques and was adapted in Japan to produce a versatile paste.

- Natto Origin - Natto fermentation involves Bacillus subtilis and originated primarily in Japan, used as a nutritious food since prehistoric times.

- Historical Usage - Miso was historically used as a seasoning and preservative in Japanese cuisine, while natto served as a protein-rich staple for rural communities.

The cultural significance and fermentation processes of both miso and natto reflect Japan's profound culinary heritage.

Key Ingredients and Preparation Methods

| Key Ingredients | Miso primarily uses soybeans, salt, and koji mold (Aspergillus oryzae), while natto is made from soybeans and Bacillus subtilis bacteria. |

| Preparation Methods | Miso fermentation involves inoculating cooked soybeans with koji and allowing maturation for months to years; natto fermentation requires steaming soybeans followed by inoculation with Bacillus subtilis and fermentation at warm temperatures for 24 hours. |

Fermentation Processes: How Miso and Natto Differ

Miso fermentation involves koji mold (Aspergillus oryzae) breaking down soybeans and grains into a savory paste over several months. Natto fermentation uses Bacillus subtilis bacteria, resulting in sticky, stringy soybeans with a distinct aroma after 1 to 3 days.

- Miso employs Aspergillus oryzae - This mold breaks down starches and proteins, creating umami-rich compounds.

- Natto uses Bacillus subtilis - This bacterium produces a mucilaginous texture and strong flavor unique to natto.

- Fermentation duration - Miso takes months to mature, whereas natto typically ferments within days.

Microbial Cultures: Aspergillus Oryzae vs Bacillus Subtilis

Miso fermentation primarily relies on the mold Aspergillus oryzae, which breaks down soy proteins into amino acids, creating a rich umami flavor and smooth texture. Natto fermentation uses Bacillus subtilis, a bacterium known for producing a distinctive sticky texture and strong aroma through its enzymatic activity on soybeans. The differing microbial cultures result in unique biochemical processes, influencing flavor profiles, textures, and nutritional benefits of each fermented soybean product.

Texture, Flavor, and Aroma Comparison

Miso presents a smooth, creamy texture with a salty and umami-rich flavor, often accompanied by a subtle sweetness and earthy aroma. Natto features a sticky, stringy texture with a strong, pungent flavor and a distinctive ammonia-like aroma that can be polarizing.

The texture of miso makes it ideal for soups and sauces, creating a mellow, balanced taste profile in dishes. In contrast, natto's unique consistency and robust flavor are prized in traditional Japanese cuisine for their probiotic benefits and bold sensory experience.

Nutritional Profiles: Miso vs Natto

Miso, a fermented soybean paste, is rich in protein, vitamins B2 and K, and minerals such as zinc and manganese, supporting digestive health and immune function. Natto contains higher levels of vitamin K2, essential for bone health, along with nattokinase, an enzyme that promotes cardiovascular wellness.

The fermentation process in miso produces beneficial probiotics and antioxidants, enhancing gut microbiota diversity. Natto's fermentation yields strong probiotic strains like Bacillus subtilis, which improves nutrient absorption and supports metabolic functions.

Culinary Uses in Japanese Cuisine

How do the culinary uses of miso and natto differ in Japanese cuisine? Miso is primarily used as a flavorful base for soups, marinades, and dressings, offering a rich umami taste that enhances various dishes. Natto is commonly consumed as a fermented soybean side dish, known for its strong aroma and sticky texture, often served over rice or incorporated into sushi rolls.

Health Benefits and Potential Risks

Miso and natto are fermented soybean products with distinct health benefits; miso is rich in probiotics and antioxidants that support gut health and immune function, while natto contains high levels of vitamin K2 and nattokinase, which promote cardiovascular health and bone density. Fermentation in both enhances nutrient bioavailability but miso generally has lower sodium content compared to traditional natto. Potential risks include histamine intolerance from miso and the strong ammonia-like odor of natto, which may affect palatability and cause digestive discomfort in sensitive individuals.

Related Important Terms

Koji Inoculation

Miso fermentation relies heavily on koji inoculation using Aspergillus oryzae to break down soybeans into amino acids and sugars, creating a rich umami flavor. Natto fermentation primarily depends on Bacillus subtilis fermentation rather than koji, producing a sticky texture and strong aroma distinct from koji-inoculated miso.

Bacillus subtilis Proteolysis

Miso fermentation primarily involves Aspergillus oryzae for enzymatic breakdown, whereas Natto relies on Bacillus subtilis to drive proteolysis, resulting in a distinct umami flavor and enhanced bioavailability of amino acids. Bacillus subtilis in Natto promotes robust proteolytic activity, generating peptides and free amino acids crucial for its unique texture and nutritional properties.

Short-chain Peptide Profile

Miso exhibits a rich diversity of short-chain peptides generated by Aspergillus oryzae fermentation, enhancing its umami flavor and bioactive properties. Natto, fermented by Bacillus subtilis, produces distinctive short-chain peptides with fibrinolytic activity, contributing to cardiovascular health benefits.

Aged Miso Umami Index

Aged miso boasts a higher umami index due to prolonged fermentation that enhances glutamate and amino acid concentrations, creating a richer, more complex flavor profile compared to natto. Natto's fermentation primarily develops strong aroma and sticky texture through Bacillus subtilis, but its umami intensity remains lower than that of aged miso.

Nattokinase Activity

Natto fermentation produces high levels of nattokinase, an enzyme renowned for its potent fibrinolytic activity that supports cardiovascular health by breaking down blood clots. In contrast, miso contains lower nattokinase concentrations but offers a broader spectrum of enzymes and probiotics beneficial for digestion.

Polyglutamic Acid Yield

Natto fermentation produces significantly higher levels of polyglutamic acid compared to miso, enhancing its viscosity and health benefits. Miso fermentation yields lower polyglutamic acid but offers a unique profile of amino acids and umami flavor compounds.

Miso Funk Aroma Compounds

Miso fermentation develops complex funk aroma compounds such as amino acids, organic acids, and esters that create its characteristic savory umami profile, differentiating it from natto, which produces stronger ammonia and sulfurous smells due to Bacillus subtilis activity. The koji mold (Aspergillus oryzae) used in miso fermentation enzymatically breaks down soy proteins and starches, generating a balanced and rich flavor palette favored for soups and sauces.

Branched-Chain Amino Acid Ratio

Miso fermentation yields a balanced branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) ratio with a slight emphasis on leucine, enhancing flavor complexity and nutritional benefits. Natto, however, exhibits a higher isoleucine content relative to valine and leucine, contributing to its distinctive aroma and potent health-promoting properties.

Pure Spore Fermentation (PSF)

Pure Spore Fermentation (PSF) in soybean fermenting highlights stark differences between miso and natto, with miso relying on Aspergillus oryzae spores to develop a rich umami flavor and smooth texture, while natto depends on Bacillus subtilis spores to create a sticky, pungent product rich in vitamin K2 and nattokinase enzymes. PSF enhances controlled microbial growth, resulting in consistent quality and distinct biochemical profiles that influence nutritional benefits and culinary applications of these traditional Japanese fermented foods.

Miso vs Natto for soybean fermentation. Infographic

cookingdiff.com

cookingdiff.com